|

by Sarah Morris  Ida B. Wells at the end of the 19th century. Photo retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Ida B. Wells at the end of the 19th century. Photo retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. From a young age, I have always had a passion for writing and how beautiful it can be. One thing I realized as I was growing up is that writing can be more than just writing a story or completing an essay assignment. Pen on paper, words typed on a screen, can be used to accomplish something, persuade someone to change their opinions, or in Ida B. Wells’ case, fight for racial equality and justice. Because I have a love for writing, I was truly inspired by Wells’ use of literature to work towards earning the American people’s care towards a cause she believed in. She was brutally honest about the terrible abuse African Americans suffered through and discrimination they faced even after the Emancipation Proclamation. Ida B. Wells was an African American journalist who fought for equal treatment of races and sexes. This activist may best be known for her anti-lynching crusade. Born into slavery in Mississippi in 1862, Wells saw racial injustice throughout her entire life, particularly when living in the South. Though “declared free by the Emancipation Proclamation shortly after her birth … racial prejudices were still very prevalent in the time that she grew up in Mississippi.”[1] She witnessed the mistreatment of her friends because of their race, as well as being ill-treated herself. Ida Wells had to grow up quickly, cutting her childhood short at only 16. Her parents, “as well as one of her siblings, fell ill and died of yellow fever, leaving Wells on her own to provide for her younger sisters and brothers.”[2] To provide for them, she convinced a local school that she was 18 years of age and landed a job as a teacher. She cared for her siblings this way until 1882, when she moved the family to Memphis, Tennessee, to live with her aunt.

1 Comment

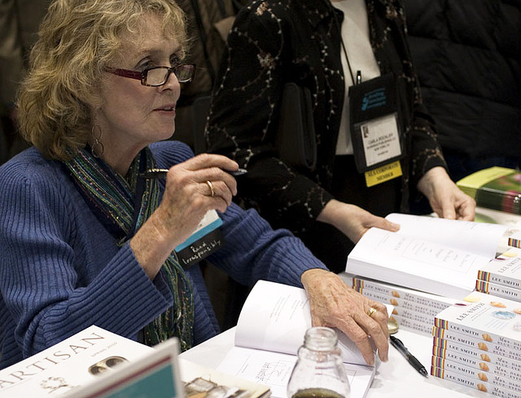

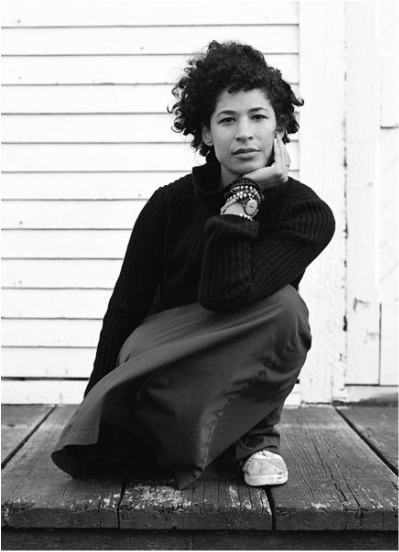

I grew up in a household that was, and still is, passionate about food. For us, food meant the unity of family. It was there through times of laughter, heartache, and of course those creative moments when we craved something that was amazing. However, food wasn’t just about sustenance—it was something much deeper than that. It became spiritual. “Growing up as a child, food was very rewarding for us,” my mother, Jean Jacquet, stated as she stared off into her childhood memory as if it were physically in the room with her. Jean was a private chef and caterer prior to being diagnosed with stage III breast cancer. From a very young age she knew that cooking was her passion, as she saw the joy it could bring to the people she served. From as early as four years old, Jean always found herself gravitating towards the kitchen. “One day I was hungry as a child—and I’ll always remember this,” she recalls. “I was four years old and my mom left some pork chops on the stove to go gossip with the neighbor. I went to the stove, and the pork chops were cooking, so I was flipping them over and stuff. I didn’t have a clue as to what I was doing as far as flipping the pork chops over. When [my mother] came in her eyes got all big and she hurried up and grabbed me away from the stove. By that time the pork chops were already done.” Jean had begun to learn the basics of cooking by watching her mother and grandmother cook. It wasn’t until she was about nine years old that she created her first successful dish. “My mom had to get a job and go to work, and so she didn’t make anything and we didn’t have any leftovers. So I went and got some rice because I remember I used to watch her cook it. I washed it, put it on the stove, and then turned the stove off to let it steam. I went to go watch TV. By that time, my mind had gotten off of how hungry I was, and I totally forgot about the pot of rice. When [my mother] came home she looked on the stove and saw the pot of rice and she said, ‘Who been in the kitchen cooking?’ I got scared because I thought she was going to whoop me because I used to always get in trouble for going to the stove and trying to cook,” Jean laughed. “She looked at the rice and tasted it and asked again who made it. I couldn’t lie because I knew I would get a whooping for lying, so I told her I made it since I was hungry. I started crying so she knew I was hungry and wouldn’t whoop me and she said ‘Baby, this is the best pot of rice I ever tasted!’”  Dorothy Allison at the 2008 Brooklyn Book Festival in New York City. Photo by David Shankbone. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Dorothy Allison at the 2008 Brooklyn Book Festival in New York City. Photo by David Shankbone. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. When I read Dorothy Allison’s fiction for the first time, I felt enraged. Not for Allison depicting the truth, wherein another rapist gets away with his crime, but the fact that I was used to this narrative. I thought, “I shouldn’t feel used to such disgraces.” Nevertheless, every year, countless men get away with rape, and Allison does not sugarcoat this fact. She shares the truths that we would rather ignore, like every other noteworthy Southern writer. Consider, for instance, Eudora Welty’s and Flannery O’Connor’s popular works. In “Why I Live at the P.O.” (1983), Welty presents familial discord at its ugliest. When Welty’s protagonist, Sister, is outcast by her family, she “marche[s] in where they were all playing Old Maid and pull[s] the electric oscillating fan out by the plug . . . [and] snatche[s] the pillow [she’d] done the needlepoint on right off the davenport from behind Papa-Daddy.”[1] Then, in O’Connor’s “A Good Man is Hard to Find” (1953), when the Misfit, a heinous serial killer, kills his latest victim, he shares nefarious thoughts that other people would leave unsaid: “‘She would of been a good woman,’ The Misfit said, ‘if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.’”[2] Accordingly, Welty and O’Connor make us uncomfortable, force us to confront our inner demons, and haunt our imaginations long after we read their final words. Unlike Welty and O’Connor before her, however, Allison gives us a glimpse at other atrocities. With brutal realism, Allison’s writing portrays domestic abuse, sexual violence, and incest. In her seminal work Bastard Out of Carolina, a finalist for the 1992 National Book Award, she debunks rape myths, which originate from rape culture.[3] Allison writes from personal experience. Like her heroine, Bone, she lived with her rapist—a man who should have protected and loved her—her stepfather. Allison never allowed this injustice to stop her from pursuing her career or helping others. Whether Allison is working at a Women’s Center or writing, she fights for women’s justice. On April 11, 1949, Allison was born in Greenville, South Carolina, where she spent her childhood and young adulthood. Allison describes South Carolina as “a hardscrabble state. I still have family, although for the most part they have scattered and decimated. It’s a rough place. But pretty. Very pretty.”[4] Allison’s statement speaks to the paradox of the South. Although the South’s sprawling terrain is beautiful, it is the home of the Civil War, the Jim Crow laws, and other political debacles. This past casts an ever-present shadow over life in the South. This public confrontation often reflects the discord happening inside of private homes. Similar to her heroine in Bastard, Allison was born out of wedlock. Her mother worked as a waitress to make ends meet and eventually married a truck driver. When she was five years old, Allison’s stepfather began to rape her and this sexual violence continued into her young adulthood.[5] Despite the sexual violations and the physical abuse she suffered at the hands of her stepfather, Allison never lost sight of the life she wanted—a life that excluded her rapist. Although no one in her family had ever graduated high school or attended college, she went to Florida Presbyterian College and received her Bachelor’s degree in Anthropology.[6] Shortly after receiving her degree, she attended a meeting at Florida State University’s Women’s Center, and she found her true passion: listening to other women’s stories and sharing her own. Allison remarks upon the impact the Women’s Center has had on her life: “I would not have become a writer if I hadn’t stumbled into that Women’s Center. I don’t know that I would have managed to survive.”[7] Since she walked into the Women’s Center, she has established herself as a central Southern writer.  Minnie Fisher Cunningham. Photo retrieved from Wikipedia. Minnie Fisher Cunningham. Photo retrieved from Wikipedia. Growing up in an Italian-American family, I’ve always had a sense of pride in my heritage and admiration for the risk that my grandparents took in chasing the American Dream. My grandparents migrated from Sicily in the 1960s to escape economic and social oppression. Prior to meeting their husbands, my grandmothers, Nonna Sofia and Nonna Rosetta, journeyed to America independently in search of a better life. Their independence, courage, and perseverance allowed them to break free from the gender restrictions of Sicily while finding their own way in the Land of Opportunity. My grandmothers’ strength and drive are a source of inspiration as they have overcome barriers that were placed before women. My grandmothers are living proof of how successful feminists, like Minnie Fisher Cunningham, have been in paving the way for women to gain equality. Born on Fisher Farms, Texas in 1882, Cunningham worked tirelessly to fight for women’s rights. Born to a prominent planter who had a brief sitting in the Texas House of Representatives, Minnie Fisher Cunningham was introduced to the political stage at a young age. She received a solid education while being homeschooled by her mother and later graduated from the University of Texas at Galveston as “one of the first women to receive a degree in pharmacy in Texas.[1] During her short bout as a pharmacist, Cunningham experienced an injustice that would turn her determination away from practicing medicine and towards fighting for social justice. Cunningham found out that although she received a prestigious medical degree from UT, “her untrained male colleagues made twice her salary” which pushed Cunningham into becoming a “‘suffragette,’” as she called herself.[2] Minnie Fisher Cunningham’s upbringing and events in her early life led her to become a promoter of women’s rights who focused on ways to improve society in general even in the face of opposition. 4/7/2016 0 Comments Like a Whirlwind: Lee Smith Lee Smith. Photo courtesy of American Libraries, the magazine of the American Library Association, reprinted under a Creative Commons license. Lee Smith. Photo courtesy of American Libraries, the magazine of the American Library Association, reprinted under a Creative Commons license. Most academics will admit, if pressed, that long-term research on a particular subject can sometimes spoil it for you. If that subject isn’t awfully rich and hearty, the hours (let alone days, weeks, years, and even decades) of analysis can render the subject into a flat, distorted, unrecognizable thing. But even after 25 years of scholarly work on Lee Smith’s stories, I still find her fiction as fascinating as I did when, in the spring of 1991, I read my first of her novels, Oral History.[1] Struck by the power of that book, I bought and devoured Fair and Tender Ladies,[2] which would become and remain one of my top five novels ever. Since then, I have with great pleasure read everything Smith has written. The voices she has generated have become background music to my own life, as they have for so many readers. Like other fans of Smith’s writing, I have been continuously drawn to her Southern (often Appalachian) characters and settings, periodically rereading Fair and Tender Ladies, for example, to revisit the mesmerizing Ivy Rowe at her farm in Sugar Fork on Blue Star Mountain. But perhaps beyond the appeal of these richly rendered people and places, Smith’s language itself leads readers into moments of the sublime, her prose an artful combination of Appalachian and Southern dialects with poetically crafted diction and syntax which, as Longinus explains of sublimity, “tears everything up like a whirlwind.”[3] In a missive to her deceased father, Ivy reminisces about how he would take her and her siblings up the mountain to collect birch sap, how he once cut bark from a tree for them to taste and warned Ivy, “Slow down, slow down now, Ivy. This is the taste of spring.”[4] Through these lines, Smith’s language both offers a glimpse into Ivy’s nontraditional spirituality, springing from her perceptive relationships with nature and people, and transports the reader through its very sound and texture.  Helen Keller, circa 1904. Photo copyright United States Library of Congress. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Helen Keller, circa 1904. Photo copyright United States Library of Congress. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Having been born in Florida and raised in the South, the school systems I attended were always eager to share stories of those who impacted where we live now. A reoccurring name each year was Helen Keller, but she was always described as the woman who was blind and deaf, but did stuff anyway. Because her story was always oversimplified, I was inspired to learn about her on my own, so hopefully I can provide a more involved summary of Keller and her life. Helen Adams Keller was born June 27, 1880 in Tuscumbia, Alabama. Although born with the ability to see and hear, she endured an illness in her early childhood that compromised her senses. Helen contracted an illness, called "brain fever" at the time, that rose her body temperature. Although we are still not certain the specifics of the disease, some experts believe it may have been scarlet fever or meningitis. After the fever broke, she didn't react when the dinner bell rang, or when a hand was waved in front of her face. Helen had lost both her sight and hearing when she was only nineteen months old. Because of this, Helen Keller also slowly lost her ability to speak, though this did not render her silent. Keller had become a very wild and unruly child during this time. She tormented her eldest sister, Martha, and often threw raging tantrums against her parents. Many family relatives felt it would be best for the family if they institutionalized her.[1] Helen was unable to effectively communicate, but at age six, her family hired a tutor, Anne Sullivan, to help her become literate. They began small with finger spelling, a style of teaching that did not grab young Helen’s attention forvery long. Being forced into lessons she had trouble following, Helen Keller started to throw more tantrums in defiance of her new teacher. Sullivan later demanded that Helen be separated from the rest of the family as the teaching was in progress, so the two moved to a cottage of Anne’s father, Thomas Macy. Because Anne’s help and a fresh environment, Helen gradually began to recover her communications skills, and she began to show an interest in creative writing.[2] This hobby challenged the ableist expectations conceived by society. At this time period, most other children with communication difficulties were incarcerated in mental facilities, like what the other members of Helen’s family had recommended.  Dolly Parton at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, April 2005. Photo by Tech. Sgt. Cherie A. Thurlby, USAF. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Dolly Parton at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, April 2005. Photo by Tech. Sgt. Cherie A. Thurlby, USAF. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. As I was growing up, my family went to Pigeon Forge, Tennessee every chance we got. We would make the three-hour trek through the Great Smoky Mountains whether it was Thanksgiving break or just because my great-aunt and uncle were getting a cabin for the weekend. Every trip we devoted an entire day to go to Dollywood. Dollywood is the amusement park that Ms. Dolly Parton first opened in 1961 as Rebel Road; it was eventually reopened and named Dollywood in 1986. Her amusement park has 27 rides, including anything from major roller coasters (such as Wild Eagle, Tennessee Tornado, and Mystery Mine) to kiddy rides in the Country Fair part of the amusement park. In addition to rides, the park has daily shows such as Christmas in the Smokies, Dreamland Drive-in, and Country Cross Roads. The park also has some of the best food you might ever eat. I always remember hearing Dolly Parton’s singing throughout the amusement park or taking a tour through her magnificent tour bus. The amusement park is a wonderful way to experience the impact Dolly has made and the happiness she chooses to bring to the world. She is a country idol especially in her small hometown of Sevierville, Tennessee, and she is someone my family has adored every since I can remember. Over the holiday break I overheard my grandmother and great-aunt excitedly discussing a new movie that was going to be airing on TV. The movie was Coat Of Many Colors, the life story of Dolly Parton. Every single person living in my house sat down the next night to watch the much-adored Dolly as a little child and learn the story of her coming to be. Though the movie first aired on December 10, 2015 and was supposed to be a one-time air on NBC, it received so many views that the channel decided to air it again on Christmas day. Coat of Many Colors tells the story of Dolly’s “rags to rhinestones” childhood and shows how it is not about how much you own in life but who you spend life with. After the movie ended and all my family was ooh-ing and ahh-ing over it, I started to realize how much of an influence she is to all people.  Rebecca Walker. Photo by David Fenton. 2003. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Rebecca Walker. Photo by David Fenton. 2003. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Familial relationships can be complicated. Every family has their own problems, some worse than others. When Rebecca Walker was eight years old, her parents divorced, which concluded with her growing up in two very different environments. Her father, Mel Leventhal, is Jewish in faith and an accomplished New York lawyer. Her mother, Alice Walker, is the author of the classic American novel The Color Purple and a prominent figure in the feminist community. Rebecca’s life experiences—understanding her own identity as black, white, and Jewish—and living in the shadow of her mother have uniquely colored her writing. Rebecca is accomplished in her own right as an American novelist, activist, and artist. She graduated Cum Laude from Yale University and is credited for introducing the concept of Third Wave Feminism in an article she wrote for Ms. Magazine at the age of twenty-two.[1] Rebecca is the author of three books, including NY Times best seller Black, White And Jewish (2001); the acclaimed Baby Love: Choosing Motherhood After a Lifetime of Ambivalence (2007); and, Adé: A Love Story (2013). She has been the editor for several anthologies, including To Be Real: Telling the Truth and Changing the Face of Feminism (1996), What Makes a Man: 22 Writers Imagine the Future (2004), One Big Happy Family (2009), and Black Cool (2012). Both her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Ms. Magazine, Glamour, The Washington Post, Newsweek, Vibe, Essence, Interview, and many other notable magazines and literary collections. She has addressed audiences at hundreds of universities and corporate campuses, including top Ivy League colleges Harvard, Brown, and Yale. It was announced in 2014 that her novel, Adé: A Love Story, is in talks to become a movie, with Madonna signed on to direct the film. She has also worked on and appeared in the Amazon Prime hit, Transparent.[2] 12/4/2015 0 Comments Writing Wrongs: Alice Walker Alice Walker, 2007. Photo by Virginia DeBolt. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Alice Walker, 2007. Photo by Virginia DeBolt. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Deep in the South–thick air, saturated foods, warbling tongues behind plump lips–the reminiscent pain of slavery presses on like an iron against a board. As Southerners of all races, we make efforts to assimilate all cultures (so that we may not return to our brute roots of horrible subjugation) by a fusion that creates a fragrant, hearty soup from which we may all freely, safely taste. However, Southern society frequently fails to reflect on our ugly past in such a way that truly respects and understands what has happened. The type of literature that Alice Walker and authors like her produce is vital to making the final connection between cultures, so that we may submerge ourselves as deep as possible into a position of suffering that we will have never specifically known so that we might reflect with sincerity. I find it to be revolutionary and, perhaps, healing that Walker not only gives insight into the hardship that African Americans have suffered, but also gives a delicate, truthful face to the grievances of women. I cannot possibly stress how important it is that she illuminates the transcendence of misogyny cross-culturally. It is certainly no coincidence that women akin to Alice Walker often write about specific traumas from a very raw place. Many women, including myself, use writing as a voice of expression, redemption, and victory in a world that often denies us the fruits of our rightful validation and triumphs. As Southern women, it seems we have yet to conquer the final frontier of freeing ourselves from the gnarled grasp of sexist abuse and trauma that readily produces poetic sorrow and poised narration of a life from which we, at times, cannot protect ourselves.  Vernice Armour, 2006. Photo retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Vernice Armour, 2006. Photo retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Imagine it’s hot—desert hot—and the strange place you’re in is dangerous. Every stranger is a potential threat. The conversations around you take place in a tongue you don’t understand, and menacing looks are being directed your way. Suddenly, the dangerous nature of this place decides to reveal itself. The rounds begin to fly, splintering the wood of the structures around you. Death buzzes past, centimeters from your head. The screams of terror are understood in every language. The enemy has you pinned down, and you realize there is no escape for you and your fellow war fighters. You reach for the radio and call for close air support. The iconic sound of the Cobra’s blades can be heard chopping the air in the distance, fast approaching, and carrying with it your hope of survival. Vernice Armour, the first female African American combat pilot, swoops in from overhead in the Marine Corps AH-1W SuperCobra. Wielding the awesome power of the 20 MM Gatling cannon and the side mounted Hellfire missiles, she clears a path for the Marines to escape. This is not where this incredible story begins, however; its humble roots lay in Tennessee. The daughter of Gaston C. Armour and Authurine Armour, Vernice Armour was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1973. After her parents divorced when she was three, her story changed settings to Memphis, Tennessee. It is here she would flourish and reach her true potential and prove herself to be an exemplary individual from an early age. |

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed