|

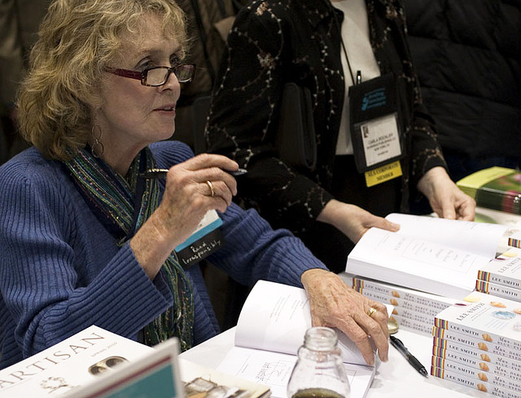

4/7/2016 0 Comments Like a Whirlwind: Lee Smith Lee Smith. Photo courtesy of American Libraries, the magazine of the American Library Association, reprinted under a Creative Commons license. Lee Smith. Photo courtesy of American Libraries, the magazine of the American Library Association, reprinted under a Creative Commons license. Most academics will admit, if pressed, that long-term research on a particular subject can sometimes spoil it for you. If that subject isn’t awfully rich and hearty, the hours (let alone days, weeks, years, and even decades) of analysis can render the subject into a flat, distorted, unrecognizable thing. But even after 25 years of scholarly work on Lee Smith’s stories, I still find her fiction as fascinating as I did when, in the spring of 1991, I read my first of her novels, Oral History.[1] Struck by the power of that book, I bought and devoured Fair and Tender Ladies,[2] which would become and remain one of my top five novels ever. Since then, I have with great pleasure read everything Smith has written. The voices she has generated have become background music to my own life, as they have for so many readers. Like other fans of Smith’s writing, I have been continuously drawn to her Southern (often Appalachian) characters and settings, periodically rereading Fair and Tender Ladies, for example, to revisit the mesmerizing Ivy Rowe at her farm in Sugar Fork on Blue Star Mountain. But perhaps beyond the appeal of these richly rendered people and places, Smith’s language itself leads readers into moments of the sublime, her prose an artful combination of Appalachian and Southern dialects with poetically crafted diction and syntax which, as Longinus explains of sublimity, “tears everything up like a whirlwind.”[3] In a missive to her deceased father, Ivy reminisces about how he would take her and her siblings up the mountain to collect birch sap, how he once cut bark from a tree for them to taste and warned Ivy, “Slow down, slow down now, Ivy. This is the taste of spring.”[4] Through these lines, Smith’s language both offers a glimpse into Ivy’s nontraditional spirituality, springing from her perceptive relationships with nature and people, and transports the reader through its very sound and texture. When she is asked about the influences on her writing, Smith often recalls, as she does in her recent memoir Dimestore,[5] that as a child she would listen from a corner of her father’s “Five and Ten Cent Variety Store”[6] in Grundy, Virginia, to the stories and conversations that filled the air of the place. Her still-growing oeuvre of fiction evidences her absorption of the idioms and cadences she overheard during those early years. Later, during her undergraduate years at Hollins College, studying creative writing under such figures as Louis D. Rubin, Jr., she honed her burgeoning talent on the manuscript that would become her first novel, The Last Day the Dog Bushes Bloomed (1968).[7] Even in that early work, one can see evolution toward the poetic quality that characterizes Smith’s fiction as a whole. In particular, Smith’s prose becomes extraordinary in her portrayals of the ecstatic moment, an instance in which a character, and often the reader, experiences a heightened or even transcendent sense of being--a challenging experience for any writer to render effectively, but which Smith does powerfully. For her characters, these moments can be generated through intense sexual encounters, serendipitous experiences with nature, Holiness Church snake-handling, and direct personal glimpses into the spiritual realm. In an interview with Smith in September of 2011, during which I asked her about the frequent exploration of this ecstatic moment in her fiction, she relates insights that she gleaned at Hollins during her formative college years: I have been writing all my life, and I think this is my primary motivation--it’s a way to get into this altered state, which becomes addictive over time, I guess. I’m certainly hooked now! Annie Dillard[8] and I have talked about this a lot; she says writing is “like prayer.” All I can say is that it takes you out of yourself entirely, that it literally transports you…. When I was a sophomore at Hollins College, we had a visiting writer named Colin Wilson, …one of Britain’s “angry young men,” [who] had gotten famous overnight at age 24 by publishing a book named The Outsider in 1956. Here he discussed the work of “outsider” writers such as Camus, Sartre, Hesse (wow!), William James, and Van Gogh (wow!), [and set] forth his own theories of alienation and creativity…. We read [and examined the work of these and other writers] …for what Colin Wilson called the “peak experience”[9] that moment of enlightenment when the “veil parts”[10] and we perceive reality very intensely---often through sex, or after a serious illness, I remember he said---or in grief, as I have since realized myself.[11] Such glimpses beyond ordinary life appear over and over again in Smith’s work, through language crafted to draw the reader into the experience of these relatively rare moments. Florida Grace Shepherd, of Saving Grace, transcends the ordinary during her first sexual encounter, with her half-brother Lamar during a revival, and again later when she handles live coals as her deceased mother once did: “The Spirit comes down on me hard like a blow to the top of my head and runs all over my body like lightning. My fingers and toes are on fire. O Lord it is hard to breathe and I am scared Lord, I am so scared but I will let my hands do what they are drawing now to do and it does not hurt, it is a joy in the Lord as she [Grace’s mother] said. It is a joy which spread all through my body.”[12] Exploring the cosmic/personal human experience through charismatic characters, settings both familiar and alive, and language with the power to transport, Lee Smith’s body of work makes an impact both on the literary world and on the individual reader. When I wish for the company of a friend, someone who can articulate the universe from a homely perspective like my own, I sometimes read the ending of Fair and Tender Ladies, where the now-elderly Ivy, transitioning from life into death, proclaims lyrically, “there is a time for every purpose under heaven The hawk flys round and round, the sky is so blue. I think I can hear the old bell ringing like I rang it to call them home oh I was young then, and I walked in my body like a Queen [sic].”[13] Tanya Long Bennett has been a professor of English since 2001 at University of North Georgia, where she also currently serves as Interim Dean of Honors. Her book "I have been so many people": A Study of Lee Smith's Novels was published in 2014 by University Press of North Georgia. She has been greatly inspired over the course of her career by writers like Lee Smith, Don Delillo, Vladimir Nabokov, Iris Murdoch, Maxine Hong Kingston, and Louise Erdrich, as well as by many students. Over the years, she has been intellectually, creatively, and emotionally nourished by her husband, Chuck, and their three kids, Zach, Luke, and Tyler. [1] Lee Smith. Oral History. New York, NY: Ballantine, 1983. [2] ---. Fair and Tender Ladies. New York, NY: Ballantine, 1988. [3] Longinus. “On Sublimity.” Classical Literary Criticism. Eds. Oxford, UK: D.A. Russell and Michael Winterbottom. Oxford UP. 145. [4] Smith. Fair and Tender Ladies. 76. [5] Lee Smith. Dimestore. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin, 2016. [6] Ibid, 4. [7] Lee Smith. The Last Day the Dog Bushes Bloomed. New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1968. [8] Annie Dillard was a classmate of Smith’s at Hollins and remains a close friend. Dillard is the author of the Pulitzer Prize winning Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974), among many other works of memoir, fiction, and poetry. [9] Smith’s quotation marks. [10] Smith’s quotation marks. [11] Lee Smith. Email interview with Tanya Long Bennett. September 11, 14, and 21, 2016. [12] Lee Smith. Saving Grace. New York, NY: Ballantine, 1995. 271. [13] Smith. Fair and Tender Ladies. 317.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed