|

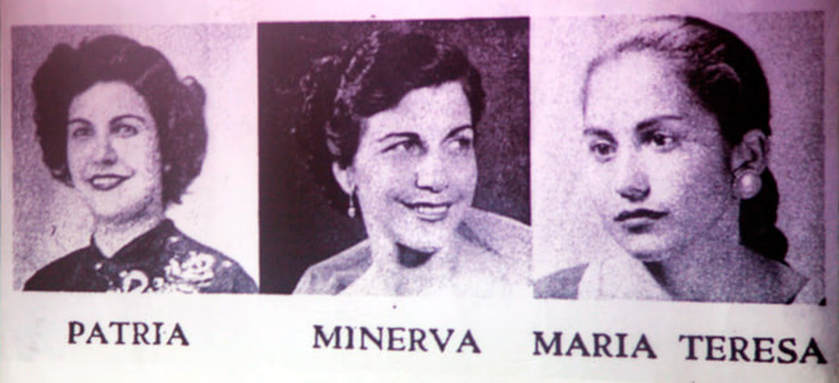

by Elize Villalobos As the new year begins, it is a hard necessity that we reflect upon the tumultuous political events that have taken place in the U.S. and across the globe that have shaken people’s collective sense of security. However, for today, rather than analyze circumstances that you already know are dire, it seems prudent to share a story which might revitalize your hopes for this new year, a story in which organized resistance thwarts oppression in the end. The heroines thereof were three sisters: Patria, Minerva, and Maria Teresa Mirabal. It should be noted that their home country, the Dominican Republic, belongs to the Global South, a popular term in transnational and postcolonial studies used to refer to “developing” nation-states that share a history of colonialism or imperialism; the term also describes the “deterritorialized geography of capitalism’s externalities and means to account for subjugated peoples within the borders of wealthier countries,” and “the resistant imaginary of a transnational political subject that results from a shared experience of subjugation under contemporary global capitalism.”[1] Considering these expansive, broad meanings of a Global South, it is only right that these iconic sisters be included as we pay tribute to great southern women of the past and present. The Mirabals were revolutionary activists who stood against the regime of dictator Rafael Trujillo around the mid-1900s and became national martyrs in the process.[2] They had another sister, Dede, who was not involved with their cause due to her personal values and her controlling husband’s opposition.[3] However, even without her aid, her three siblings would manage to change Dominican history and leave an indelible mark on the culture and politics of all of Latin America.

Notably, the Mirabal sisters were all born quite close to Trujillo’s rise to power in 1930; Patria, Minerva, and Maria Teresa were born in 1924, 1927, and 1936, respectively.[4] They were raised in an affluent yet conservative, insular area of the Republic, but their upbringing and environment would stifle neither their strength nor their intelligence. Contrary to social norms of the time, the three would be well-educated thanks to their mother who, despite, or because of, her own illiteracy, argued on their behalf for their right to an education. She convinced her strict husband that if Patria were educated on her path to become a nun, her sisters should be afforded the same opportunity.[5]

2 Comments

11/30/2017 0 Comments Katie Leikam, LCSW: Transforming the Decatur LGBTQIA Community Through Affirming Therapyby Cameron Williams Crawford  I met Katie for the first time when she and her husband hosted us at a housewarming party at their new home. They had recently moved into our neighborhood, and my husband, a realtor, had worked as their agent. “I think you’ll like the Leikams,” he told me on the ride over, “They’re good people, and it seems like you and Katie might have some of the same interests.” Turns out, he was right. We arrived at the party, where Katie graciously welcomed us at the front door. She then ushered us into the kitchen and told us to help ourselves to the taco buffet and the wine slushies. I knew in that moment that we would be friends. Apart from discovering we shared a mutual love of most things epicurean, I also learned that night that Katie, a licensed clinical social worker, was in the process of opening her own private practice in Decatur, where she would specialize in treating LGBTQIA, gender non-conforming, and transgender clients. She has since opened her practice, and it is thriving. Katie mostly grew up in Griffin, Georgia, but because her father worked as a salesman, her family moved around quite a bit; for a time, she also lived in Florida and North Carolina. Eventually, she found her way to back to Georgia, where she would go on to earn a Bachelor of Science degree in Psychology from Georgia State University and a Master’s in Social Work from the University of Georgia. It was during her time in grad school that she gained her first experience in social work. In 2005, Katie worked the Meals on Wheels program as part of her internship with the Athens Community Council on Aging. That same summer, she served as a parent aid for DFACS, supervising visitation with foster children and their biological parents. Katie considers her time with DFACS as both challenging and rewarding. In one particular experience she described to me, Katie remembered going into a home where she discovered some needles and dirty diapers. “I had to tell the kid that he couldn’t see his mom that day,” she told me, “and he was really upset and tried to punch me. That was a difficult experience.” One of her favorite memories, however, is when “a mom set up a manicure for her daughter” during a supervised visit at a library: “She brought nail polish and a foot spa, all sorts of stuff, and gave her daughter a manicure, and that’s what they did for their visit. It was really cool.” After she finished her Master’s, she was a program coordinator for foster kids; she monitored foster homes, made checklists, and made sure “the homes were in order and the kids were taken care of behaviorally.” One of the reasons why Katie chose a career in social work was because, as she said to me, “when I was in high school, I was seeing a licensed clinical social worker. I absolutely loved him, and he made a really big difference in my life.” At first, Katie said, she wanted to be an English teacher, until she decided she would much rather “help people who were having issues and concerns.” by Elize Villalobos  Henrietta Lacks. Photo by OI a.urabain. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Henrietta Lacks. Photo by OI a.urabain. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Throughout history, there has always been a strange human impulse to reduce people solely to the tangible impact that they have left on the world. A life filled with untold hopes and dreams becomes a mere collection of facts and figures, associated only with the legacy that fortuity has seen fit to ingrain in our collective consciousness. One of the most striking cases of this in modern history is the story of Henrietta Lacks, a woman who neither consented to a procedure from which the fields of cellular biology and technology would be changed, nor lived long enough to know of her profound impact on the world. Perhaps the most insightful encapsulation of the moral essence behind Lacks’ tale is found on a single page before the prologue of the book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot. There, a quote by Elie Wiesel, a famous survivor of the Holocaust, reads: “We must not see any person as an abstraction. Instead, we must see in every person a universe with its own secrets, its own treasures, with its own sources of anguish, and with some measure of triumph.”[1] Often known solely by her cell line’s name, HeLa, Lacks was a normal woman who died from an abnormally aggressive cervical cancer. The first human immortal cell line would be cultivated from the cells of her initial tumor, a development that directly and indirectly facilitated enormous strides in medicine and science.[2] However, for far too long, Lacks herself was reduced to nothing more than a clinical subject, either treated as incidental to her cells or else entirely eclipsed by them. Yet, steps towards rectifying that injustice have been made by many devoted journalists and authors, chief among them Skloot, whose book recounts Lacks’ biography and posthumous legacy in great detail, and upon which the recent movie of the same name starring Oprah Winfrey was based. The gains made from her cells have long been acknowledged and celebrated, but it is necessary and right to remember her as the individual she was while alive, not merely as an abstract figure whose untimely demise is but an afterthought to the large-scale, long-term benefits it ultimately provided. 8/11/2017 0 Comments Rose-Colored Girl: Hayley Williamsby Lindsey Castille  Hayley Williams, lead vocalist of the American rock band Paramore, at Rock im Park 2013 in Nuremberg, Germany. Photo by Sven-Sebastian Sajak. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Hayley Williams, lead vocalist of the American rock band Paramore, at Rock im Park 2013 in Nuremberg, Germany. Photo by Sven-Sebastian Sajak. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. While listening to Paramore’s After Laugher, the band’s fifth studio album, I can’t help but feel nostalgic. I first discovered Paramore and their lead singer almost exactly ten years ago, when I was just thirteen. Paramore’s music and Hayley Williams’ powerful voice quite literally changed my life. I have seen Paramore live more times than I can count on one hand. Hell, I dyed my hair cherry red for four years because of her. Hayley Williams is a role model not only to me, but to thousands, maybe millions, of other girls and women. Her image as a fiery and fearless individual remains iconic. What started in Franklin, Tennessee as a teenage afterschool funk cover group successfully emerged as a mainstream pop rock band. Paramore has toured with musical heavyweights including No Doubt, Green Day, Tegan and Sara, Reliant K, New Found Glory, and Fall Out Boy, and has had six major headlining tours.[1] Paramore has also been nominated for multiple major awards, including an American Music Award, Billboard Music Award, MTV Video Music Award, People’s Choice Award, Teen Choice Award, and four Grammy Awards. In 2014, they won “Best Rock Song” at the Grammy Awards for “Ain’t it Fun,” a single from their self-titled album.[2] Paramore has sold millions of records and is considered a huge commercial success. Williams is surprisingly a very private person and likes for her personal life to remain as such. In her professional life, Williams has collaborated with several bands and solo artists including New Found Glory, B.o.B., Zedd, Chvrches, and Taylor Swift. She has also been featured on several movie soundtracks, including Twilight, Transformers: Dark Side of The Moon, and Jennifer’s Body.[3] Apart from her music, Williams is a successful entrepreneur, businesswoman, and philanthropist. She is passionate about beauty, creating and collaborating on both makeup and hair product lines. In 2013, she collaborated with MAC Cosmetics to create a small makeup line in her name.[4] In 2015, she introduced “Kiss-Off,” an online series on Popular TV showcasing beauty and music.[5] In 2016, she released her eagerly anticipated hair dye brand, Good Dye Young.[6] Williams has also participated in campaigns to raise awareness and funds for breast cancer research.[7] by Elize Villalobos  Phyllis Frye. Photo retrieved from Alchetron, The Free Social Encyclopedia for the World, reprinted under a Creative Commons license. Phyllis Frye. Photo retrieved from Alchetron, The Free Social Encyclopedia for the World, reprinted under a Creative Commons license. Every so often, sociopolitical situations come along that remind us that we must never take our civil rights for granted. For many people in the U.S., particularly people of color, religious minorities, LGBTQ+ folk, and anyone who falls within an intersection of those three umbrella groups, the months between the presidential election and today have served as a sobering reminder of the societal prejudices and institutional discrimination that still deny them the benefits of full equality in American society. Indeed, trans people, specifically, have continued to face setbacks this year. The news that Trump’s administration rolled back the Obama administration’s transgender bathroom policies, which allowed trans students to use whichever restroom matched their gender identity, was undoubtedly a blow to LGBT rights.[1] However, even more sickening than this particular revival of institutionalized transphobia is the violence that the trans community continues to face: so far, ten transgender people have been murdered in 2017, most of whom were targeted simply because they were transgender.[2] In light of these recent issues, as well as the other ongoing struggles of the transgender community, it is perhaps a natural reflex to want to take a moment to recognize a past leader of the trans rights movement so that we may be heartened and regain some hope and energy for the future. Therefore, on that topic, it is a great pleasure to highlight Phyllis Frye, a transgender woman who has been one of the most instrumental figures in fighting for and furthering trans rights during the last several decades. I admit that I had not heard of Frye until she was recommended as a subject for this profile. However, upon researching her, I was completely awed by her story and courageous advocacy. A fitting dénouement to her storied career as an activist, in 2010, the mayor of Houston, Texas, Annise Parker, appointed Frye as a municipal court judge with unanimous consent from the city council.[3] Although Frye is one of the first openly transgender judges to serve in the States, she says that she is aware of at least two other trans judges in other parts of the country, such as Vicki Kolakowski, who became a judge in California 15 days before Frye became one in Texas.[4] Regardless, Frye’s accomplishment, as well as Kolakowski’s, is a milestone for the transgender community. As has been intimated in media coverage of Frye’s appointment, there is something approaching poetic justice in the fact that a woman who was once explicitly targeted by Houston law for simply existing as herself is now an authority thereof.[5] Along with her judgeship, Frye manages the law firm Frye and Associates, which “provide[s] a variety of legal services for the LGBT and Straight-Allies community;” Frye herself now solely represents transgender people to help them navigate the unique legal difficulties that come with being trans.[6][7] by Emily Garmon  I first met Catherine Thomas when I was interning for Resurgens Theatre Company during my senior year of college. Catherine had been the skilled costumer for Resurgens for the last few years. When I first asked her to be profiled on Beyond the Magnolias, Catherine told me she was incredibly flattered. On the day of our interview, she shared with me again her excitement to be considered a remarkable southern woman. Catherine viewed past profiles on Beyond the Magnolias, and she felt she was certainly “not in this class of people.” From the little I did know about Catherine, I already knew this was not true. By the end of our interview, I learned Catherine is a wife, mother, cancer survivor, costumer, actress, singer, fencer, baker, avid reader, and so much more. After getting to know more about Catherine’s diversified talents and interests, it became clear she is quite the Renaissance woman. After seeing Catherine’s artistry at work first hand in Resurgens’ productions of The Alchemist, Volpone, and Sejanus, I was convinced she had been formally trained. When I asked her how long she had been costuming, Catherine responded she has been sewing since she was 10 years old, and the first to model her original costuming were her Barbie dolls. Catherine described the costumes and dresses of her early years as “pretty hideous.” When I asked her what attracted her to sewing and costuming, she simply said, “I have always been fascinated with what people wear and why.” Astonishingly, Catherine is completely self-taught through trial-and-error, as well as reading numerous books on the subject. Despite her authenticity and sumptuous abilities, Catherine feels her lack of formal training creates “gaps in what she can do.” Her supposed limitations are nonexistent to any onlookers of her work. However, Catherine does give herself some credit – when describing her thorough research process while she is costuming, she proudly proclaimed, “I know what I am doing historically.” It must be said that academia, language, history, and other cultures are no stranger to Catherine. She attended the University of South Carolina, where she studied Foreign Language and minored in Comparative Literature. Her talents, as well as her educational background, have served her well while working with Resurgens Theatre Company. by Victoria S. Jacquet  Melissa Greeson was just nineteen years old when she discovered she was pregnant with her first child, Kailey Lynn. She was nervous at the thought of what others would think about the pregnancy, and also not knowing what to expect out of the experience. However, her excitement to meet Kailey quashed any last bit of that anxiety. “I actually called my mom to my house, and I gave her a present [because] we were really excited. I was her baby who was about to have a baby,” Greeson says. Never would she have imagined the traumatic events that unfolded on the day of her beautiful Kailey’s birth. Greeson was in labor for nearly nineteen hours with Kailey Lynn: “I was exhausted, obviously, and towards the end of her labor [there were] signs that something was wrong. [Kailey] was in distress—I was in distress, but again I was only nineteen so I really didn’t know what was going on. I just knew that it wasn’t the fairytale that everybody talked about and not what I envisioned as becoming a mom for the first time.” By the time Kailey Lynn entered the world, she was not breathing. Whatever joy Greeson experienced immediately turned into a terror when Kailey was placed on oxygen to assist her respirations: “In time she started breathing on her own, which I didn’t expect because she was purple. She didn’t cry for a while, and she was really lifeless, so I was extremely scared. [Kailey] spent fifteen days in the NICU with ups and downs. They told me that I should basically pull the plug and take her off of life support—that she would be a vegetable, and I would never forgive myself for allowing her to live, which was hard to hear. I chose not to go down that route. In time they took her off of life support and she lived. I don’t know how, but it’s definitely a blessing.”

by Cameron Williams Crawford

Jesmyn Ward, 2011. Photo by Jesmimi. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Jesmyn Ward, 2011. Photo by Jesmimi. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

I should probably begin by stating that this post is basically my love letter to Jesmyn Ward, who, since I discovered Salvage the Bones a couple of years ago, has quickly become one of my favorite and most-admired writers. Ward’s writing is exquisite; it’s graceful and lush with metaphor. She is the kind of rare storyteller able to find splendor in savagery, who can make you smile at the same time that she breaks your heart. In her relatively short career as a writer, she has produced a number of important pieces of work for feminism, African American literature, and for Southern literature (which, let’s be honest, largely continues to be the domain of white men). As both a scholar and enthusiastic bookworm, that is incredibly exciting for me. So, imagine my delight (read: fangirl freakout) when I learned that Ward would be reading from her new collection of essays and poems about race, The Fire This Time, at the Carter Center here in Atlanta this past August. Joined by other great writers and contributors to the collection—including Carol Anderson, Jericho Brown, and Kevin Young—the event was, to say the least, an edifying experience. In the wake of the recent shootings of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling, it was especially poignant. The Fire This Time, which takes its title from James Baldwin’s 1963 book of essays on race in America, The Fire Next Time, “channel[s] Baldwin’s urgency toward reflecting on black life in America” and carries on a discussion that remains very necessary.[1] In an interview with Audie Cornish on NPR’s All Things Considered, Ward addressed the need for continuing to talk about race: “If we don’t, [and] if it’s a conversation that we walk away from because we’re too tired of having it, then nothing really changes.”[2] Such is the nature of all Ward’s writing, really; though here she may be specifically referring to race, a similar sentiment persists throughout her work. Her two novels and her memoir each carry on essential conversations about the cruel realities of race, poverty, and gender in ways that are sometimes gut wrenching, yet honest and, importantly, not without a sense of hope.

by Amber Richards  Reese Witherspoon in the Oval Office on June 25, 2009. Official White House Photo by Pete Souza. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Reese Witherspoon in the Oval Office on June 25, 2009. Official White House Photo by Pete Souza. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Reese Witherspoon is not only an absolutely stunning and talented actress, she is a role model for many teenage girls and women across the world, including myself. From her home-grown roots, she is as down-to-earth and Southern as she comes across in movies like Walk The Line or Sweet Home Alabama. Laura Jeanna Reese Witherspoon (which is her real name) was born on March 22, 1976 in “New Orleans, Louisiana but raised in Nashville, Tennessee. She is the second child Dr. John Draper Witherspoon, “a military surgeon specializing in ear, nose and throat,” and Mary Elizabeth “Betty” Witherspoon, “a registered nurse who later became a pediatric nurse.” [1] Living in Nashville, Reese was surrounded by famous country musicians, inspiring artists trying to make their way, and actors and actresses that had made it successfully, which somewhat helped her choose acting as a career. Reese’s story is not close to any “rags to riches” tale; she was an upper-class young lady who “attended an all-girls private school and was later a debutante,” [2] but she had the ambition and motivation to earn fifty-one awards (including an Academy Award for Best Actress in 2005) and be nominated for eighty-seven awards.[3] Although acting was not her first choice for a career—“Reese went to Stanford University for her freshman year in college (which she did not complete)”[4]—she took a leap of faith and put her whole education on hold for to pursue acting, which would soon impact her life in the most positive and rewarding ways. As an actress, she chooses roles that empower women; through her roles, such as those in Legally Blonde, Walk the Line, Sweet Home Alabama and Cruel Intentions, she shows that any woman can accomplish any dream that comes to mind. “I choose the roles I do because I want my daughter to see what strong, accomplished women are like,” Reese stated in an interview.[5] With three children now, one girl and two boys, she says that they “get the point” on how important it is to follow their dreams and not let anyone or anything stop them, and this is a message she strives to share with the whole world as well.[6] In another interview, she said that if she had one quote she would like the share with other women, it would be, “The thing about ascending is that you have to keep going. The thing about going beyond, is that you have to go. You have to keep rising.”[7] This is truly inspiring, helping and motivating women all across the world with progressing toward any goal, and Reese Witherspoon herself lives by the same quote daily and shows how true it really is. 9/20/2016 0 Comments A Beautiful Mind: Carson McCullersby Alexis Sharbel  Carson McCullers. Photo by Carl Van Vechten. July 31, 1959. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Carson McCullers. Photo by Carl Van Vechten. July 31, 1959. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. When I think of Carson McCullers, two words come to mind: beautiful and chaotic. McCullers was so fluent in her writing and descriptions; one feels connected not only to her characters, but also to McCullers herself. Part of that feeling is because McCullers often included personal elements—including the frustrations and confusion she often experienced—in her writing. To help understand this, particularly McCullers’s use of queer identities in her fiction, one must first look at her life as well as her writing. Carson McCullers was born as Lula Carson Smith in 1917 in Columbus, Georgia. She changed her name to simply Carson Smith when she moved to New York. Carson originally moved to New York to attend Julliard to pursue a career in music, mostly the piano.[1] She then became Reeves McCullers in 1937. McCullers was known for her struggles with rheumatic fever, which caused her to experience multiple strokes and physical issues. This is part of the reason as to why McCullers strayed from music and pursued her passion for writing. Most of her best novels and stories were written while she was in the throes of sickness and sometimes bedridden.[2] Carson McCullers was married for only four years before the two separated. The main issue that occurred while they were together: they both were alcoholics and suffered reoccurring depression. They also both identified themselves as bisexual.[3] This part of McCullers life was “destructive,” as she and her husband were both very sexually active with men and women alike.[4] They also were somewhat in competition with their writing, and often Carson was in the lead. They divorced in 1941, largely due to jealousy and competition. Both Carson and Reeves fell in love with the same man, David Diamond, which caused Carson and Reeves to tear apart while competing for Diamond’s love.[5] |

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed