|

by Cameron Williams Crawford

Jesmyn Ward, 2011. Photo by Jesmimi. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Jesmyn Ward, 2011. Photo by Jesmimi. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

I should probably begin by stating that this post is basically my love letter to Jesmyn Ward, who, since I discovered Salvage the Bones a couple of years ago, has quickly become one of my favorite and most-admired writers. Ward’s writing is exquisite; it’s graceful and lush with metaphor. She is the kind of rare storyteller able to find splendor in savagery, who can make you smile at the same time that she breaks your heart. In her relatively short career as a writer, she has produced a number of important pieces of work for feminism, African American literature, and for Southern literature (which, let’s be honest, largely continues to be the domain of white men). As both a scholar and enthusiastic bookworm, that is incredibly exciting for me. So, imagine my delight (read: fangirl freakout) when I learned that Ward would be reading from her new collection of essays and poems about race, The Fire This Time, at the Carter Center here in Atlanta this past August. Joined by other great writers and contributors to the collection—including Carol Anderson, Jericho Brown, and Kevin Young—the event was, to say the least, an edifying experience. In the wake of the recent shootings of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling, it was especially poignant. The Fire This Time, which takes its title from James Baldwin’s 1963 book of essays on race in America, The Fire Next Time, “channel[s] Baldwin’s urgency toward reflecting on black life in America” and carries on a discussion that remains very necessary.[1] In an interview with Audie Cornish on NPR’s All Things Considered, Ward addressed the need for continuing to talk about race: “If we don’t, [and] if it’s a conversation that we walk away from because we’re too tired of having it, then nothing really changes.”[2] Such is the nature of all Ward’s writing, really; though here she may be specifically referring to race, a similar sentiment persists throughout her work. Her two novels and her memoir each carry on essential conversations about the cruel realities of race, poverty, and gender in ways that are sometimes gut wrenching, yet honest and, importantly, not without a sense of hope.

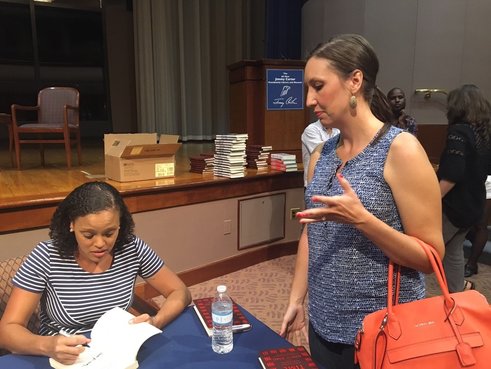

Me with Jesmyn Ward at the Carter Center event for The Fire This Time, where I am telling her way more than she probably cared to know about my ideas for teaching Salvage the Bones. Me with Jesmyn Ward at the Carter Center event for The Fire This Time, where I am telling her way more than she probably cared to know about my ideas for teaching Salvage the Bones.

Ward was raised in DeLisle, a small, rural town located along the Mississippi coast. She earned her MFA in creative writing from the University of Michigan in 2005, where she won a number of awards for her fiction.[3] Around this same time, Hurricane Katrina battered the Gulf Coast, causing extreme loss of life and displacing more than a million residents. Ward and her family were among those devastated by the storm, forced to flee their home when the rising floodwaters threatened their lives. Notably, Ward’s experiences during Katrina play an integral role in her novels, “which subtly blend the creative and the personal, the imagined and the remembered.”[4]

Ward’s first novel, Where the Line Bleeds, was published in 2008 and draws on her upbringing in a rural, impoverished, post-Katrina community on the Gulf Coast. The novel follows the lives of twin brothers, Christophe and Joshua DeLisle, who struggle to find work and relieve their family from poverty after graduating from high school. Joshua secures a job for himself working on the docks; Christophe, however, becomes entangled in a drug-dealing operation. In a review from The Austin Chronicle, Elizabeth Jackson notes the “original and subversive implications” of Ward’s style, remarking on how her prose “recalls William Faulkner.” As Jackson writes, through invoking the “(white) father of Southern letters,” Ward—a black woman writer whose fiction explores the lives of poor, rural, black families—“seems to push against the typically one-directional phenomenon of (for instance) millions of white men mimicking gut-rot Delta blues.”[5] Where the Line Bleeds, as Ward’s other work continues to do, advocates for more diverse and complex representation, particularly of people of color, in literature. Ward herself has explained, “I understood that I wanted to write about the experiences of the poor, and the black and the rural people of the South … so that the culture that marginalized us for so long would see that our stories were as universal, our lives as fraught and lovely and important, as theirs.”[6] In Where the Line Bleeds, Ward offers a compassionate, nuanced portrayal of a marginalized group of people so often reduced to demeaning stereotypes. From 2008-2010, Ward held a Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University, and in 2011, acted as the Grisham Writer in Residence at the University of Mississippi.[7] In 2011, she published her second novel, Salvage the Bones, which really began as an essay for The Oxford American that detailed her own personal account of Katrina.[8] The novel takes place over the course of the twelve days leading up to Hurricane Katrina’s landfall and tells the fictional story of fifteen-year-old Esch Batiste, newly and unexpectedly pregnant and living with her three brothers and father in “the Pit,” a poor, predominantly black neighborhood on the fringes of Bois Sauvage, Mississippi. On a personal note, I taught this novel this past semester in my Gender and Literature course. Not only did it prove to be a hit with my students (who do not always enjoy the novels I assign), it exposed them to a counter-narrative that’s too often ignored. Salvage the Bones “gives voice to the experiences of those wounded and displaced by the storm” and confronts the all-too-common response to the disaster that blames victims for not following mandatory government-issued directives to evacuate.[9] “My family has been poor and working class for generations,” Ward says in an interview with Gwen Ifill, “And we live—I live in this really small community in Southern Mississippi, where you don’t evacuate, and you have never evacuated because there are too many people in your family to evacuate.”[10] In another interview, in response to a question about why she chose to write about Hurricane Katrina, Ward says, “I was angry at the people who blamed survivors for staying and for choosing to return to the Mississippi Gulf Coast after the storm.”[11] Particularly compelling is how the novel interrogates the intersection of gender and race and explores the many ways in which cultural and historical traumas are acted out on the bodies of women. “Bodies tell stories,” says fifteen-year-old Esch, pregnant with the child of a neighbor boy who doesn’t love her and with no access to women’s healthcare or birth control. By drawing parallels between Esch’s pregnancy and the oncoming Hurricane Katrina, Ward makes conspicuous “the interactions of assumptions about race, gender, and dependency and the conscious underfunding of government that [were] evident” in the regional and national response to victims of Katrina.[12] Salvage the Bones won the 2011 National Book Award for Fiction. Ward lived through the national tragedy that was Hurricane Katrina, and her experience during the storm and its aftermath inform much of her writing. She also endured a far more personal tragedy in 2000, when her younger brother was killed in an accident with a drunk driver. Ward has spoken openly about her family’s tragic loss and how it has haunted her. On a segment from Fresh Air, Ward discusses the tattoo on her wrist: it’s her brother’s name, and it helped her deal with the despair, depression, and suicidal thoughts she struggled with following his death.[13] She has also said that she began writing as a way to honor her brother.[14] In 2013, she published Men We Reaped, a memoir that explores the lives and untimely deaths of her brother and four other young black men from her hometown. Men We Reaped is a deeply personal look at “how the history of racism and economic inequality and lapsed public and personal responsibility festered and turned sour and spread” through her hometown and others like it.[15] In the prologue, she acknowledges this story as the hardest one she’s had to write, as well as one she feels compelled to write—to make sense of her friends’ and brother’s deaths and the circumstances surrounding them, but also to share their stories, their lives, and restore “flesh to the bones of statistics.”[16] Like her other work, Men We Reaped is absolutely heartbreaking. It’s also profoundly resonant, particularly in this divisive, Trumpian political climate that pervades the entire nation, not just the South. Literature is a powerful tool for social justice, and Ward wields it decisively, giving all of her readers something to learn from: she inspires us to listen to the stories and experiences of others that are perhaps different from our own, and she encourages us to approach them with understanding and compassion. ---------- [1] “‘The Fire This Time’: A New Generation Of Writers On Race In America.” NPR, 2 Aug. 2016. [2] Ibid. [3] “Jesmyn Ward.” Lyceum Agency, 2017. [4] Ibid. [5] Jackson, Elizabeth. “Review: Where the Line Bleeds.” The Austin Chronicle, 19 Dec. 2008. [6] Bosman, Julie. “National Book Awards Go to ‘Salvage the Bones’ and ‘Swerve.’” The New York Times, 16 Nov. 2011. [7] “Jesmyn Ward.” [8] Marotte, Mary Ruth. “Pregnancies, Storms, and Legacies of Loss in Jesmyn Ward’s Salvage the Bones.” Ten Years After Katrina: Critical Perspectives of the Storm’s Effect on American Culture and Identity, edited by Mary Ruth Marotte and Glenn Jellenik, Lexington Books, 2015, pp. 207-19. [9] Marotte, Mary Ruth and Glenn Jellenik. “Introduction: Reading Hurricane Katrina.” Ten Years After Katrina: Critical Perspectives of the Storm’s Effect on American Culture and Identity, edited by Mary Ruth Marotte and Glenn Jellenik, Lexington Books, 2015, pp. vii-xiv. [10] “Writer Jesmyn Ward Reflects on Survival Since Katrina.” PBS Newshour, 24 Aug. 2015. [11] Ward, Jesmyn. Men We Reaped, Bloomsbury, 2013, p. 263. [12] Adrian, Lynne M. “Definitions and Disasters: What Hurricane Katrina Revealed About Women’s Rights.” Forum on Public Policy: A Journal of the Oxford Round Table, 22 Dec. 2007. [13] “‘Reaped’ is a Reminder that No One is Promised Tomorrow.” NPR, 24 Sep. 2013. [14] Bosman. [15] Ward, 8. [16] Jones, Tayari. “In Their Prime: Men We Reaped: A Memoir, by Jesmyn Ward.” The New York Times, 13 Sep. 2013.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed