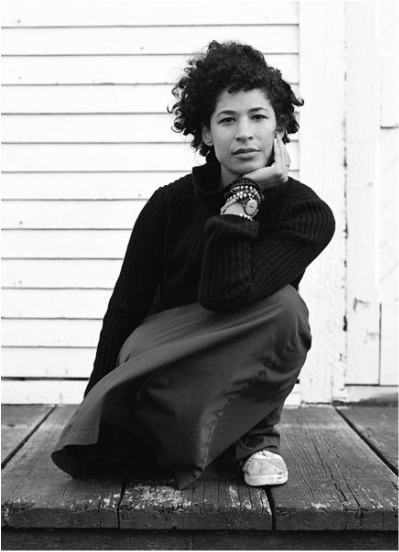

Rebecca Walker. Photo by David Fenton. 2003. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Rebecca Walker. Photo by David Fenton. 2003. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Familial relationships can be complicated. Every family has their own problems, some worse than others. When Rebecca Walker was eight years old, her parents divorced, which concluded with her growing up in two very different environments. Her father, Mel Leventhal, is Jewish in faith and an accomplished New York lawyer. Her mother, Alice Walker, is the author of the classic American novel The Color Purple and a prominent figure in the feminist community. Rebecca’s life experiences—understanding her own identity as black, white, and Jewish—and living in the shadow of her mother have uniquely colored her writing. Rebecca is accomplished in her own right as an American novelist, activist, and artist. She graduated Cum Laude from Yale University and is credited for introducing the concept of Third Wave Feminism in an article she wrote for Ms. Magazine at the age of twenty-two.[1] Rebecca is the author of three books, including NY Times best seller Black, White And Jewish (2001); the acclaimed Baby Love: Choosing Motherhood After a Lifetime of Ambivalence (2007); and, Adé: A Love Story (2013). She has been the editor for several anthologies, including To Be Real: Telling the Truth and Changing the Face of Feminism (1996), What Makes a Man: 22 Writers Imagine the Future (2004), One Big Happy Family (2009), and Black Cool (2012). Both her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Ms. Magazine, Glamour, The Washington Post, Newsweek, Vibe, Essence, Interview, and many other notable magazines and literary collections. She has addressed audiences at hundreds of universities and corporate campuses, including top Ivy League colleges Harvard, Brown, and Yale. It was announced in 2014 that her novel, Adé: A Love Story, is in talks to become a movie, with Madonna signed on to direct the film. She has also worked on and appeared in the Amazon Prime hit, Transparent.[2] Neither Rebecca nor Alice have been shy to their fans, speaking publicly about their relationship with one another. When Rebecca released her memoir, Black, White, and Jewish, in 2001, she believed to be portraying her parents in a positive manner or at least with accuracy, but they disagreed. In the book, Rebecca states that Alice’s feminist perspective influenced every area of Rebecca’s life while she was growing up. She claims that she was not allowed to play with dolls or stuffed animals for fear that they would bring out her “maternal instinct.” As young as 13 years old, Rebecca was spending weeks apart from her mother while Alice travelled for work and vacation, left in the care of neighbors with money to pay for her own meals. Alice believed, as did many Second Wave Feminists, that becoming a wife and mother was “a form of slavery” and having personal independence and freedom was a more meaningful way to spend life.[3] Her father eventually came around, clearing things up with Rebecca and even handing out copies of her book in his office.[4] Alice, unfortunately, did not. In 2003 Alice released a blog post on her official website of her version of the events, accusing Rebecca of making “wildly untrue comments,” going so far as to call what Rebecca had said “slander.”[5] Their relationship only became more tense when, in the spring of 2004, Rebecca called to tell her she was expecting her first child. All Alice could tell her daughter was that she was “shocked” and abruptly put down the phone to go and check on her garden. The rest of their conversations then took place through the impersonal forms of email and post. Alice sent Rebecca an email threatening to sabotage Rebecca’s career as a writer for statements she made publicly, and Rebecca eventually received a letter from Alice in which she resigned from the burden of being her mother.[6] When one’s private life becomes public, things only become more messy and complicated. The truth normally lies somewhere in the middle of any two stories. Alice suffered an injured ego when Rebecca expressed her true feelings, believing that Rebecca had hurt her public image as a matriarch of women and sisterhood around the world. Though Alice is a famous Second Wave Feminist, she ignored her own daughter’s experience as a victim of what Rebecca describes to be severe emotional and physical neglect. The Second Wave focused on violence in relationships, the main concern being not relationships with family but rather romantic relationships.[7] They showed us that domestic violence consists not only of physical abuse, but also verbal, emotional, sexual abuse, or any combination thereof. As feminist theories have advanced, it has become understood that these types of abuse can also occur within a family dynamic.[8] Hopefully, Alice is continuing to critique her feminist ideals, to understand that there is no wrong or right way to be a woman. Rebecca’s choice to become the opposite of her mother, a wife and maternal caregiver, is a perfectly valid choice for how one could spend their life. Rebecca uses writing as a therapy, healing in the only way she knows how. She described writing Black, White And Jewish as something she needed to do to keep her sanity intact and grow into the “next developmental stage” in her life. Whether or not her mother agrees with her writing, Rebecca was raised by a feminist writer, and she was raised to tell her truth.[9] Given the choice between being a writer and being a daughter, Rebecca proudly states “the writer wins every f*ing [sic] time.”[10] Rebecca uses her writing as a transformative tool to make art of the painful memories surrounding her relationship with her mother. Faint optimism for a healed relationship between the two lies within the fact that Rebecca has a connection with Alice through blood and name that will never be broken. As a teenager, Rebecca legally changed her last name from her father’s given name, Leventhal, to Alice’s maiden name, Walker, to connect herself to her mother “tangibly and forever.”[11] Both Rebecca and Alice believe wholly in the truth. The first thing one will notice while on Rebecca’s website is a header stating, “Openness is our greatest human resource.” Alice’s counter-article to Black, White And Jewish revolves around the idea of Malama Pono, which is Hawaiian for “Take Care of The Truth.”[12] Both Rebecca and Alice are living their own truths, butting heads in disagreement. As mother and daughter, they cannot help but see things from different perspectives. Disagreement is in the nature of family, perfectly illustrated by comments Rebecca made in an interview with The Rumpus: “Some of them [stories] will be glowing and some of them will be messy, and that’s how family is.”[13] Lindsey Castille is currently a sociology major attending the University of North Georgia in Gainesville. She is the creator and president of UNG Gainesville’s Gender Equality Club. In her first year of the club she ran several events, including a now annual drive called Lady & the Tamp, which collects women’s and children’s products for a women’s shelter. She considers herself an intersectional feminist and enjoys studying about social problems, body positivity, sex positivity, gender, and many other things considered feminist issues. In her free time she enjoys reading the classics, and her recent literary hang-up is bio-comedies. She is also interested in organic gardening, eating sushi, and petting other people’s dogs and cats. She is a vegetarian, concert enthusiast, and rabid fan of the Harry Potter series. Her future college plans include either staying on the UNG campus and pursuing a social work degree with a minor in gender studies, or attending the University of Georgia to pursue a degree in gender studies. She wants to continue in a career that helps women, however that may be. [1] Ibid. [2] "About." The Official Site for Rebecca Walker. Rebecca Walker, 2016. Web. 05 Jan. 2016. [3] Walker, Rebecca, “How My Mother’s Fanatical Views Tore Us Apart.” [4] Botton, Sari. "Conversations With Writers Braver Than Me #16: Rebecca Walker." The Rumpus. The Rumpus, 24 Mar. 2014. Web. 05 Jan. 2016. [5] Walker, Alice. "Taking Care of the Truth – Embedded Slander: A Meditation on the Complicity of Wikipedia." Alice Walker: The Official Website. Alice Walker: The Official Website, 2013. Web. 05 Jan. 2016. [6] Walker, Rebecca, “How My Mother’s Fanatical Views Tore Us Apart.” [7] Conger, Cristen. "How Feminism Works." HowStuffWorks. InfoSpace, 16 Feb. 2009. Web. 05 Jan. 2016. [8] "Definition." domesticviolence.org. Creative Communications Group and Divorce Online, 2015. Web. 05 Jan. 2016. [9] Botton. [10] Ibid. [11] Walker, Rebecca. Black, White, and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self. New York: Riverhead, 2001. Print. [12] Walker, Alice. “Taking Care of the Truth.” [13] Botton.

2 Comments

Cyntharee Powells

3/16/2018 05:22:04 pm

Rebecca , I hope that you get this message, you will always be family to me not just a (Neighbor) I love you and your mom. Lost my mom April 17, 2008. Nakiah and I miss you so much. The Rebecca I remember (15 Galilee Lane). Love you!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed